I talk to people and record it! Some call this sort of thing a podcast. I call mine Moth Minds and the premise is “interviews with high-agency humans."

Subscribe to hear the latest on a weekly(ish) basis: Spotify, Apple, Google, Amazon, and Pocket Casts.Highlights:

The best COO’s are builder generalists who can incubate things, take any curve ball that comes their way, and are complementary to the founders they work with.

The time to think about hiring a COO is when a company needs to add company-building to what has historically been a product-building focus. The secret to success is that you need to be able to attract the right candidate.

One of the most common mistakes early-stage founders make is not hiring well and then not firing fast enough when the hire isn’t performing up to par.

The best thing you can do early in your career is try a lot of different roles and industries, discover what you’re good at, and figure out how those skills could allow you to contribute to a fundamental shift already occurring in the world.

MM: Hi everybody. Today I’m joined by Claire Hughes Johnson, who is a corporate officer/advisor at Stripe and the author of Scaling People, a practical guide to company building. Claire was previously the COO of Stripe for 6 years and a leader at Google for 10. Claire currently serves on many boards including those of HubSpot, Aurora Innovation, and The Atlantic.

Our conversation covered advice for ambitious young people, tactics for hiring for and maintaining company culture, and the qualities that make for an excellent COO. I hope you enjoy.

MM: Hello Claire and welcome to the podcast.

CHG: Hello Molly. Thank you for having me.

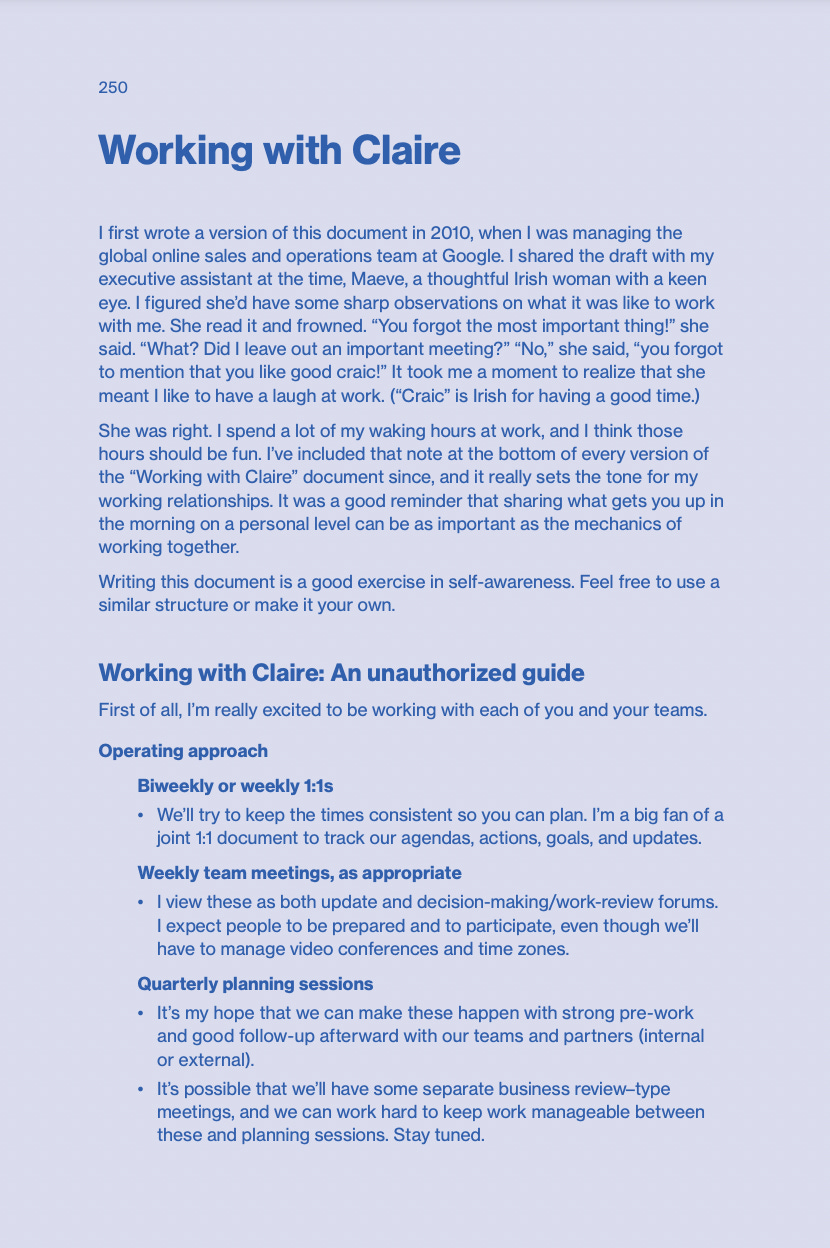

MM: Amazing. By way of introduction, my first question for you is, what was the genesis of How to Work with Me doc, and what has changed since you wrote it?

CHJ: Well that document came out of a time at Google where after, I think some good work to understand that management mattered. Google decided to start looking for great managers and showcasing them in the company. And I had the occasion to be the moderator for a panel of people who'd won this great manager award that we had. And in that panel, one of the engineering managers mentioned that she had really benefited from this user reference manual that, Urs Hölzle, who was an engineering leader at Google, had written. And I actually had never seen it and I still, I'm not sure I've ever seen it. But after the panel I thought, this is a great idea. And especially remember Google was growing quickly, then there were lots of changes in Teams and it just felt like a way to eliminate some of the anxiety when you first work with someone. But it also turned out to be a really good exercise in self-awareness. Like do I know what it's like to work with me? And try to get comments from my team on whether my document was accurate.

So I really borrowed it with pride from Urs and I'm happy to say that. I wrote the first version of it when I was at Google. I don't know what year that was, like 2010 or 2011, it might have been. It's been more than 10 years since I wrote the first version.

MM: And how has it changed since then?

CHJ: You know what's interesting? I do revisit it and I've certainly revisited it for Scaling People, my book. Not a lot has changed. One thing I remember feeling badly that I had to change was that, in the one-on-one section, so I try to set expectations about how we'll do one-on-ones and how we'll use our time. I said weekly and then as my responsibility scaled at Google and then at Stripe I had to write weekly or biweekly. Because I was like, I have to be real.

I have to admit defeat. I'm not going to meet everyone weekly anymore and that was it. That was a loss for me. But not a lot has changed. I'd like to think I've gotten a little more self-aware and tweaked some of the language. And I actually recently was on a panel for an event for Stripe with our head of sales and I recruited her to Stripe. And when she first joined, she was working for me and she told a story to the audience about how I sent her this document. And she's this Irish woman who's very like no nonsense. And she reflected to the audience that it had meant a lot to her to have a sense of me. But it's funny because at the time I remember her being like, "Oh, thank you." I mean I'm not sure what to do with this document. And so I asked her afterward, I said, "You should probably give me some feedback on whether that document was effective or not." But she seemed to benefit from it.

Anyway, so that's the story. And then now that I think about what I might change, actually, I think some of the content in scaling people writing it, forced me to write down some more of how I think about some of management and how I work with people. And so I think I could probably, I worry that the doc would get too long, but I bet I could add some more in how I think about goals, personal goals, priorities, making hard choices and decisions. I don't think there's enough about how I make decisions, but I think trying to make the document more about how we work together versus how I work is probably the next version.

MM: I love that. And that does seem like something that is revealed over time, so you need more proof points before you can add it in. What do you think is the point at which someone should write a How to Work with Me doc?

CHJ: I actually think it's a great exercise. I mean, the best thing that happened at Stripe when I shared it with some of my initial direct reports was they all wrote their own and shared it back with me. And we had a great conversation and they shared it, a bunch of them shared it with each other, their own. And so there was this team conversation happening about work styles and preferences. And I think that I would encourage people to write one as early as you feel comfortable, because there is an element of it, which is about being able to stand outside yourself and there's some vulnerability and say, "This is how I think I work. This is how I think I make decisions. This is how I like to communicate." And I remind people it's just a draft, it's going to change. But I've said to people, "I think making them mandatory is a little risky." But I think inviting people and making it a safe thing to do in a positive conversation, I think someone could write one pretty early in their career.

"[How to Work with Me docs] outline: ‘This is how I think I work. This is how I think I make decisions. This is how I like to communicate.’"

MM: It's funny, one of my first managers was an ex-Stripe and she had me write a How to Work with Me doc as an intern. I think most of it was wrong because I just didn't know. But it was a good exercise.

CHJ: But that's fine. And part of what's good about it is that it sparked the conversation. I mean that's what you really want.

MM: Absolutely. Pivoting a little bit more to talk about COO-related topics. I'm curious, what is the point at which you think companies need a COO?

CHJ: Well, I actually don't think companies necessarily need a COO. And if you look at Fortune 500 and that role, I think fewer than 30% of Fortune 500 companies have a COO. And that the role is slightly in decline if not growing in popularity. And I think it's important to have that context because the COO role has an element of an additional layer. So if you think about a leadership team, the COO is put on top of some functions in the company, which creates some leverage as they say for the CEO. But it also can have a downside, which is, is everybody at the table that needs to be at the table? Can that COO be effectively deep enough in the functions that they represent at the executive team? And some people can, while for other people I think that's a struggle — it depends on how the role is framed. So the first thing I’ll say is that I'm not sure everyone needs one.

I think where it has a fair amount of popularity for good reason is companies that are in a growth stage. Meaning they're relatively young companies, they've hit product market fit, they're starting to scale rapidly, meaning adding revenue, customers, people, hopefully revenue. And you have a situation that I think first principles, you can figure out, which is that the founder is often a technical product leader, not always, but often. And they've been dedicated as they should be to what is this product I'm building? And who's our customer? And iterating to product market fit and thinking about the business that will come out of that product market fit. But they haven't necessarily been as oriented toward building a company. And so building a product and getting product market fit is a really hard skillset. I'm not sure I could do it, so is building a company and then you're asking this founder or founders to add, it's essentially adding another full-time job onto what had been your full-time job?

And so I think the COO represents a few things there, which is someone who can come in and help partner on, sometimes it's on the product side, but more often it's on the company building the go to market, the operational side of the company in order to provide, in that case, that extra layer of experience I think is useful because a lot of those functions haven't been built and someone needs to help hire those leaders and figure out those processes. And it's really, I think, quite attractive to companies. But here's the problem. The problem is getting, I mean it's exactly your question, which is exactly when would be the moment that you would think about pursuing that role and that role, COO is a chief, it is a chief role, it is a senior experienced operator role. And if you are a young company and you're fairly small, you're not necessarily going to be able to attract that level of talent.

“I think the COO represents a few things there, which is someone who can come in and help partner on, sometimes it's on the product side, but more often it's on the company building the go-to-market… in that case, that extra layer of experience is useful because a lot of those functions haven't been built and someone needs to help hire those leaders and figure out those processes.”

And so you end up in this uncanny valley moment where you're like, "Well, I think I really need one because I'm moving into the company building phase. But who, that's a big title to give someone. And the people that I'm currently able to attract and who are helping me run the company aren't as experienced maybe in a different environment, wouldn't be a C-level executive." And so the thing I suggested and I suggest in scaling people is, think about how or when Stripe did this, which is what about a head of business operations? What about a role that is similar but maybe not so significant a title? And a way to try to hire someone and try it out, but give them some of the responsibilities of the company building and partnering with the CEO. So I really like that. And then evolving into either that person, the head of business operations might grow with the company and become a COO, or you might realize now we're big, we're 500 people we really need to bring in [a new person] and we can attract, we can attract that candidate.

And the other thing is I really encourage, and it goes back to the How to Work with Me doc. I think founders need to do an exercise in their own self-awareness, which is and their own thinking about their leadership team and saying, "What do we really need in this role?" Functionally, what do we need? But also behaviorally and capability in the leadership team. And if you do it too early, you don't really know yet what is the thing that's going to complement this group of individuals who I'm choosing to help me lead this company. And so I really think there is some value in not rushing into that for various reasons.

MM: It seems like the COO really needs to have a very firm grasp on what the culture of the company and the type of people that they want to attract. Because they're the ones recruiting so many of the ones that are going to lead up building divisions. So it's especially crucial, and I liked your strategy of trialing someone out, seeing how they are up to the role. And I'm curious, what are the qualities that you look for that you think make for a fantastic COO?

CHJ: Well, I think they're the... I mean, honestly. I think they're the qualities that I would look for in any leader, but maybe the bar is even higher. But I think the number one thing is, a person who has curiosity and integrity and really meaning they really want to learn, they have a desire to adapt and learn, and they also feel comfortable both saying what they don't know, but also saying, "I can do this thing and then they get it done." Integrity has a lot of different meanings to people. And I think there's also an element of obviously, are they excellent? Usually a COO at least is functionally deep in at least one area. And if you looked at that area, whether that's customer related work, which is often is, is there depth of experience and expertise, valid and good because they're a person who has to establish that within the new company and gain credibility.

But someone who's a learner, frankly, I think any leader you hire, you're looking for this interesting combination of confidence, but also low ego, a willingness to be wrong, listening to other people's feedback. The COO role in particular does a lot of synthesizing. "I'm hearing this, I'm hearing that, okay, I'm seeing this." Because they're really seeing a lot across the company in a way that only the CEO might see. And so you want someone who is able to really listen and then get to the heart of the matter and figure out, because often there's a decision hiding in a lot of things that happen in young companies especially, but you don't know the decision yet and you have to sort of find it. And so I think that's the other, oh my gosh, there's so many more. But yeah, excellent, learner, adaptable, listener and someone who is, understands what they know and they don't know and can, I think partner with others who, I mean to me, I'm never going to be, as I said, I'm not necessarily going to be a person who builds the best product or runs the best engineering team. But I know enough to respect that work and what it requires and what questions to ask. Do they really ask the right questions? I think maybe that's the summary.

MM: That's a good barometer. It seems like a commonality is perhaps high EQ too.

CHJ: Yeah, I think, I agree. I think that high IQ alone is often a challenge in a lot of leadership roles because people will follow people that whose intelligence they respect to a point, but they really follow people who connect with them and multiple levels. Have empathy and have heart. I think EQ is sometimes, oh, that's like the people side of things. And I feel like, no, I think it's actually being a leader who's aware that there are others that involved. Leadership-

MM: And it's what inspires loyalty too perhaps.

CHJ: I think for most people, if you feel like someone really cares about you, you're going to be more loyal to them. Eventually, I think some of these IQ relationships feel very transactional and you're right, it doesn't inspire as much loyalty.

MM: What do you think makes someone good at being a COO?

CHJ: Well, I think all the qualities we just talked about, the learning, the curiosity, the listening, the confidence though, by the way to call it, when you say, "Okay, I've seen enough data, I've seen it heard enough, we need to make a decision." I think there's an element of confidence and strong opinions loosely held. Maybe adaptability is the number one thing. Again, if we're going with the model of, we're talking about younger companies, we're talking about companies that are going to have to change and grow tremendously if they're doing well. I'm on a board where everyone talks about needing T-shaped people, but I do like that concept, which is, you have a lot of breadth of ability to operate and have enough knowledge and expertise, but you obviously have a spike in some area that you know very well. But I think being a T-shaped person who from, I often say the COO role is hard to define because it's whatever the company needs in any given moment. And what the company needs in any given moment is vastly different from week to week, month to month.

And so that adaptability and that broad leadership and problem-solving skillset and then finally, I mean, gosh, this is probably obvious, but it should be noted. They have to have a good chemistry with the CEO. There's got to be mutual respect and a collaborative. I once had an interesting interaction with someone who does a lot of executive coaching and he was talking about this critical balance for the COO CEO relationship where it can't be too simpatico because that means there's not enough complementarity happening that you need some friction. But if it has too much friction, they start to avoid each other and don't get on the same page about running the company. So you need this awareness as a unit that you're meant to be having some friction and really working out what's the best way to proceed? But you don't want to end up too far in one direction or another.

And I think it's nice to be able to articulate that because when people say chemistry, what does that mean really? I think it means a common value system even though there's complimentary skills. But I also think it means an awareness of our jobs have a role to play for the company and we need to act out that role in a way that gets to the best outcome. And that's not always comfortable, by the way. I think if you're not giving a lot of mutual feedback, I mean, any executive team with each other in my opinion, should be giving a lot of mutual feedback. But the COO-CEO need to have very frank conversations with each other about what they're doing. But the company, where we at, what do we need critical.

MM: How do you recommend that people measure their chemistry with potential founders that they might want to work with?

CHJ: Molly, you're going off after all the…

MM: Hard questions.

CHJ: I think this is really one of the things that I struggle with because I think it looks different for different people's inclinations. But I mean, a lot of people ask me to talk about my process of joining Stripe. And the reality is, I spent, I think Patrick was interviewed and said to a journalist, that he estimates he spent 50 hours with me before they made an offer. And I don't think that's wrong. This is not a one-hour interview and another one hour interview situation. This is time together, get to know you time talking about worldviews, talking about vision for the company. The best thing I think I did with John and Patrick, the Stripe founders, was, we worked on some things together. I would drive up from my house in the evening and go over things that were happening at the company with them and talk about company goals and what... We were in the rhythm of trying to make a decision together, what does it feel like?

And I do think it’s important to uncover a common value system. I have this values exercise. It wouldn't be crazy to do that exercise together, which asks: what are your top three personal values? So for me, impact is one of my values. Learning is a value. My parents are teachers. I can talk about what values really matter to me and I'm not going to be happy in any environment I'm in if I'm not having impact and I'm not learning. And I think, I found someone else, a friend of mine might say, "Well, my value is competitive, I want to win. I'm competitive." And I actually love working with people that way because sometimes I probably preference being more collaborative over being more competitive, and both of those have strengths and weaknesses. You're looking for both commonality and complementarity.

But overall, I think it's just spending a ton of time together, but not just talking, really doing some work together if you can. And then the other thing that I appreciated is John and Patrick asked to see work product of mine. And I mean I scrubbed the data, but they wanted to see emails I sent to my org at Google. They wanted to see a video I'd recorded for my team. They want to get a sense of what does it look like to work with me? Because you're bringing in someone to conceivably lead a good chunk of your company and you want to make sure that how they behave, not just with you, but as a leader is in line with how you view what leadership should look like at your company.

On picking a COO: “You're bringing in someone to conceivably lead a good chunk of your company and you want to make sure that how they behave, not just with you, but as a leader is in line with how you view what leadership should look like at your company.”

MM: I really like that. Yeah, it seems like trying to imagine what they would be like in the environment is the best way to do it. My next question is: how does the role of a COO change across different stages of a company's lifecycle?

CHJ: Well, I mentioned this. I think it is a role that in my opinion, is likely one of the most needing to adapt. Meaning it could, I mean just again, this is a first principles. Initially, you're the COO, you might have quite a lot under you because the company is smaller. When you have more generalists, you're building these functions for the first time. But as a company gets bigger, I mean, look, the scope and responsibility is so much bigger. Managing a support team of 23 people versus 2300 people and the amount of customer interaction that thereby must be happening is incredibly different. And so I think that the COO rule in some environments starts to look more CEO-like where they're not as deeply in the functions, but they might have multiple functions reporting to them, or maybe they start to graduate some functions to functional expert executive, which is more what's happened at Stripe.

And the COO role either goes away or maybe it becomes smaller and more focused on a few functions or one and running the company. I mean, you see a lot of flavors of this role, and I think that's healthy because I think it really also depends on the business model and the person's background obviously and what's needed. There's also, as companies mature, the CFO role becomes more prominent and important and some of the COO role work in a younger company actually I think ends up with a CFO in a different stage. I mean, this is hard to be specific... If I talk about a specific company, it'd be easier. But I think that constantly monitoring the context, the priorities, what scope are you looking at? What's expected of that role? And how rapidly you're growing. And if you're growing rapidly, I think you really want to look every six to 12 months at what is this the appropriate scope?

“And if you're growing rapidly, I think you really want to look every six to 12 months at what is this the appropriate scope [of the COO role]?”

Or should this individual, by the way, I think COOs at least of this type of company, I mean, I'm a builder. So I often was like, okay, I built this thing enough, it needs to go on to someone else. I'm going to go and incubate this new thing. But that's just individually, I think having really good individual context is important.

MM: It seems like the COO is one of the few roles that remains generalist and focused on zero-to-one things far past the point when the rest of the startup is still focused on that, which is a unique place to be. And also harkening back to your point, it requires some very specific qualities of actually enjoying that zero-to-one process and being good at it.

“I would say the most common COO archetype is this builder generalist who can incubate things and take any curve ball that comes in a given week.”

CHJ: Yeah, I would say that is that archetype, which is this more builder generalist who can incubate things and really honestly take any curve ball any given week. "Okay, I'll help run through this," is probably the most prominent archetype. I will say there's another archetype, which I actually would, I mean I don't know exactly when, I should know this, but Tim Cook joined Apple fairly late and he's one example. There's another example, someone like George Hu who was COO at Salesforce and Twilio. Just a deeply operational person, deeply process-oriented. And I think that is less of the adaptable generalist and more of the, again, depending on your business model. If you have a business model that's very highly supply chain, I mean, think about Apple logistics oriented or their customer delivery and interaction is incredibly complicated. You can think of maybe a DoorDash or an Instacart. You could imagine that the COO role actually has to go deeper and deeper in operational excellence and can't go and keep building new things. And in that case, maybe that's in a product that you do that. I think that's another archetype.

MM: Yeah it so depends on the business model.

CHJ: That's right.

MM: Cool. My next question is: how does the operating model of a company change from one phase to another? So one to 10, 11 to 50, and then 51 to 100?

CHJ: Well, I would think one to 10 and even maybe 11 to 30 or 40. The operating model is pretty organic. And that makes sense because you don't have a business yet, you don't have the product necessarily yet. And so you're really iterating what you are. And so getting into some rhythm of how you operate or you can't forecast if you're like, well, yeah, our main goal is to see if we can sell this thing. But focus on that and then you can start. So I think early on it's pretty organic. It happens by osmosis because you're often, whether you're in the same room physically or virtually, everyone is communicating with everyone. There's a lot of being able to just see it all transparently. And so there's less of a focus needed on, does everyone know the same information? Do we all follow the same recruiting process or the same decision process?

Like the values of the company, these unconscious beliefs and values of the culture are in the water, they're in the air, they're coming from the founder, everyone's absorbing them and everyone's in it together. The minute that you can't really comfortably have a conversation, so maybe 20 people. You're starting to say, okay, we can't actually be in a room together making a decision where everyone can participate and maybe people can watch. But that's when I think you have to start thinking about how do I codify some of these things that were implicit? And a lot of operating model is not taking some structure and imposing it on chaos. It's actually making things that are implicit more explicit and codifying them, the things you've already probably been doing in a way that they can then be repeated by people who are not the current people in the company.

“Like the values of the company, these unconscious beliefs and values of the culture are in the water, they're in the air, they're coming from the founder, everyone's absorbing them and everyone's in it together. The minute that you can't comfortably have a conversation (~20 people), you're starting to say, okay, we can't actually be in a room together making a decision where everyone can participate.”

That's literally it. Scale is just like, we have a way to repeat excellence with different unique individuals at the table. And that requires really being thoughtful about, well, what process do we use? How do we make decisions? What do we value when we think about our product priorities? What are the metrics that matter? And then honestly, I don't think some of the core operating, the best operating models really replicate. So you don't have one really, it's organic. Say you're about 30 to 40 people, you're starting to establish one. If you create the right backbone, then I think that next phase, you can really just Google's OKRs, everyone at the company replicates all the way from the individual to the executive team to the company level. That same framework that you're using to prioritize, they can scale really pretty far. I think the thing that changes, I guess my final point would be once you're getting into the 100s of people, you start to add in some more formal businessy stuff. Quarterly business reviews.

I mean, I hope by then you've got your dashboards that are actually live and synchronous and you don't have to sit and pull the data and look at it. You're automatically getting it on your home screen thing. But I think some of the business process stuff that happens with a real scale, IT systems, the data management, a lot of the security work, the business review work, the things that are more mature public company would need to have lockdown, that's another phase. And that, again, it can depend on the company, but I think some companies go too quickly into let's run ourselves like we're bigger. You don't need all that stuff as much when you're a few hundred people.

But then when you start to have a lot of layers of management, a lot of complexity. The more complexity to have, the more you need to say, well, this is how we do things. Because keeping velocity is really about alignment and having tools and mechanisms that keep you, whether that's a backend data, we all have the same data, or whether it's a way that we review success and we deem this is a successful effort, this isn't, those things need to be consistent or else you will not be able to handle the complexity.

MM: I really like the litmus test of: can you all fit in a room and actually make a collective decision? Because it seems like a lot of companies only realize that they needed to codify their values after they’ve been breaking a little bit.

CHJ: Yeah, you hire some new people and they're like, the new people don't know how to operate. And you're like, well, why? Did anyone tell them?

MM: That's a good way of putting it. My next question, I'm curious, when you're advising early-stage founders, what are the most common mistakes you see them making? And what topics do you spend the most time helping them on?

CHJ: I mean, mistake is, we're all in a learning process. And I wouldn't say these are all mistakes. I mean, I think I am certainly guilty of some of them when I was first building teams. But most of the conversations I have with founders are about their role. So what are things only they can do? And are they delegating and scaling themself? Or about their leadership team? Who do they have? Do they have the right structure for their business? What do they need? How do they think about attracting and hiring the leaders they're going to need for the next phase? And I think in that, a sub bullet of that and an area where, I wouldn't say it's a mistake, but I do think some founders aren't yet confident on their pattern match on talent. And they have individuals who are not scaling or who are not successful in their roles, and they're giving them more and more time to try to work it out and prove themselves.

“I do think some founders aren't yet confident on their pattern match on talent. They have individuals who are not scaling or who are not successful in their roles, and they're giving them more and more time to work it out and prove themselves. But as a young company, you actually have less time to help people who are having performance issues.”

And actually as a young company, you actually have less time to help people who are having maybe some job performance issues. And so I end up talking a lot about helping them to validate, and usually they just need confidence. I'm like, no, that person doesn't sound like they're working out in that role, you have to do something. And so that's a lot of the conversations. And then we talk about this, what you've just been pushing on, when should they start to bring in some more structure? Everyone thinks structure is going to kill the culture. And I'm like, well, if you actually build structures that honor the culture, in fact, it's going to save the culture. And so I have to tell them enough stories to say, let me just paint the picture for you that actually is going to be better, it'll be better.

“Everyone thinks structure is going to kill the culture. And I'm like, well, if you actually build structures that honor the culture, in fact, it's going to save the culture. And so I have to paint them enough stories for them to see that it is actually going to be better.”

So that's a lot of the conversations. The other, I wouldn't call it a mistake, but I think it's a common challenge for anyone who's a newer leader, manager, founder, which is, you feel this great burden to have answers. People are looking to you for, what's the plan? What's the vision? What are we doing next week? And you feel this pressure to have all the answers and just not succumbing to that. I mean, of course you have, I hope, the vision but not succumbing to this pressure and being able to say, "You know what? I don't know." Or me, let's talk to someone who's been looking at that issue. There's a certain reminding them they don't have to be perfect, and that actually the humility to acknowledge what they don't know is going to be really critical because, I mean, the best founders are constantly calling for expertise and advice and learning themselves. And I feel badly when I see folks who I think are feeling like they're the bottleneck on everything because they've decided they have to be involved in everything because they're supposed to know everything.

MM: It comes back to that humbleness again, it's a universal good quality.

CHJ: It's humility, but it's also humility with just the right amount of confidence. And that's a hard balance to get, especially early in your career.

MM: Speaking of being early in your career, what advice have you given to young Stripes or young Googlers about the most impactful things that they could do to build their careers?

CHJ: Yeah. I mean, I did a fireside chat with Elad Gil at Stripe not that long ago. And he made a very good comment on something I had said. So I'll try to say it and then I'll add in Elad's very good comment. I mean, the main thing is that, when you're early in your career, depending on the macro environment of the world and the economy, there's a lot of pressure to, everyone starts to be a little like, oh, we've all got to go into VC or consulting or banking or. It's this thing that happens, and that happens in college as you're graduating. It happens I think if you go to a professional school, there's like the hot places to work or the hot jobs. My advice is, do the work to understand your strengths, what you're passionate about, where you could add value — not what does everyone else want to do — but what could you do? Resist the mass.

“My advice is: do the work to understand your strengths, what you're passionate about, where you could add value — not what everyone else wants to do — but what could you do? Resist the masses.”

Yet, I think there's two things that Elad would add in, and I would agree. One is be smart about what is happening in the macro environment? Where are the interesting places to work and have an impact in society? I mean, the obvious thing to say right now if I were a young person interested in having an impact in the world is that I would want to be involved with generative AI and what it's going to mean for society. And that, by the way, could look a lot... It could look like a policy or a legal side angle. It could look like a technical technology angle. It could look like an education angle. But really be aware of where expertise is going to be needed and where you're interested and try to match those things. And then a lot also was like, and be ready to work hard.

But I think there is also bad advice around just following your passion. Look, and I did this in my career. I went into government and politics. I was really interested, but I had to have my eyes wide open, I was not going to make a lot of money. And if your passion is writing, my brother's a writer, go and try to be a writer, but you have picked one of the hardest paths in the world. Or you know what I mean? And don't get so idealistic. Be realistic, be a pragmatist. Understand the macro, understand the trade offs you're making, understand what matters to you. But the more that you can do the homework of the world around you and yourself and the match of those two things, the earlier, the better.

MM: Yeah, I love that advice. I think it’s wonderful. And the macro thing is interesting too, because I almost feel like it's about finding your niche in whatever is the current tidal wave where you find something that you can do for the long term and enjoy and learn and get really good at and known for.

CHJ: That's the other thing. Don't put [too much] pressure [on yourself]. I had so many different jobs in my twenties. I mean, so many. I think the best thing I did, Molly, was I tried things out and then I would move on. I think the other thing is people get stuck. Don't get stuck if you realized, "Oh, this isn't actually my path. I'm just going to do this." I did so many different things, and my mom luckily had said to me, "Well, you have until you're 30 to figure it out." And then I later on, I was like, "How about till I'm 50?"

MM: Yeah. Sunk cost fallacy is very real, especially when you're young and you have very little work experience, you're like, "I've sunk six funds, I have to keep doing it." It's like, no, you don't. Are there any other trends that you're excited about other than generative AI as tidal waves that you think that young people could ride?

CHJ: By the way, one other piece of advice I would give people is, I really wish I'd kept more of a journal. The beginning of the Working with Me doc essentially of what I was learning about what I was good at, what was I not good at? What did I enjoy doing? I'm not talking about every week. Yeah, I'm talking about every few months just write down some things you've learned about yourself, professional, well, personally and professionally, actually both. Get a doc together that you can have for the rest of your life and consult as you learn about who you are.

“Get a doc together that you can have for the rest of your life and consult as you learn about who you are.”

In terms of trends or what I'm interested in right now, I mean, the broader trend is really understanding technology and what it means for the human condition. And I think generative AI is the most recent example of that. And in my mind, I try to separate, there's trends, I'm going to say Web3 or whatever, that to me are a form of a trend, which is, yeah, this could be a way that we use technology or think differently about how it plays out for business or society.

But then there's atoms and bits. So what are the bits that are changing? I mean, the really fundamental thing that's changing that's making generative AI so interesting is the compute power is on a log scale just getting so much more powerful. And that's the fundamental thing you want to pay attention to. It's not how you're using the compute power. But what is that implication of Moore's law, which we've studied now for decades, and understood for how accessible the power of technology will be and how it will evolve. Generative AI being very key example of that, if that makes sense. So I think understanding fundamentals and then doing good thought experiments on, okay, if that's the case, and if there's a new large language model that's being trained every 18 months, that's a pretty fast cycle.

“So I think understanding fundamentals and then doing good thought experiments on, okay, if that's the case, and if there's a new large language model that's being trained every 18 months, that's a pretty fast cycle.”

I mean, I'm on the board of a few companies where, and which is funny because I don't think I'm particularly a futurist, but I find myself saying to the company, we have a whole set of mental models and attitudes about our current product that this is the way, for example, you do marketing today. Or this is the way that you do clean tech analysis and integration. And I was like, there's not enough thinking like three years from now that actually could be completely turned on its head by not needing the same human involvement. And are we actually thinking enough about our future state and what we might need to do now to disrupt ourselves? And we're in one of those internet finally taking off kind of moments. And that has implications for every corner of how we work and how we live.

MM: It's a very first principles framing of, “how will we change and shape the future?” And it also makes me wonder as my last question for you: what are your favorite things about the culture of technology and what would you change? How can we think bigger and identify the kind of fundamental shift opportunities you mentioned?

CHJ: My favorite thing about the culture of technology is the constant change and people feeling really energized by constant change. I'm like that. I mean, I'm not a deep technologist, but I am someone who loves change. I love having to rethink, relearn, and I love being around people who are really comfortable with, wow, the way I thought about things five years ago is going to be not the same. I think that's a great... So that and also the mutual support. When you've worked in tech as I have now, oh my gosh, for more than 20 years, if you call people for help, even in a competitor, they will help you. They will give you contacts, they will give you ideas, they will tell you, oh, I had that problem, here's what I did. And I think that Silicon Valley, and by now an extension of that to people who are just working on building new things, maybe it's just entrepreneurs.

But there is this, we're in it together, and we are going to help each other. If we are asked, we will help. I love that. I love that. I think what I don't love is really, actually, I think my book encapsulates some of this, which is, sometimes we get so excited about the rate of change and the ability to envision a very different future that we decide that we can throw out all the things we know. Invent everything new. What is management? Or how do I run an organization effectively? And in fact, if you look at the history of management conceptually, it hasn't changed. I mean, Holocracy is one movement, but for hundreds of years, there's traditions of hierarchy, and I don't mean like patriarchal hierarchy, but companies having management structures and using that to get leverage to run themselves.

And there are people who know how to do that well. And there are companies that are extremely well run that are traditional, that should be respected and studied. And so I just sometimes wish tech would not do this thing it does, where it's like, well, I'm going to reinvent everything. And I'm like, well. And I understand why they do, because technology can solve so many things that a traditional company hasn't thought about solving. But there are still people involved. I mean, maybe AI will change that, but there are still people involved. And if there are people involved, there are known practices, and we should not reject them because they make it better for the humans in the experience. And if you think about being in an environment of constant change, you want to make it better for the humans in that experience because they are going to perform better. In the interest of better results, let's not throw out some of the things we've learned from history.

MM: Yeah, it's balancing when to embrace creative destruction and when to hold back.

CHJ: Exactly. That's exactly it.

MM: Wonderful. Well, thank you so much for coming on the podcast, Claire. I really enjoyed this interview and I highly recommend everyone read your book Scaling People, published by Stripe Press.

CHJ: Thank you so much for having me, Molly. It was a pleasure.

Subscribe for more episodes to come: Spotify, Apple, Google, Amazon, and Overcast.

Share this post