My main learning after a full year of Moth Fund has been to bet on unabashed capitalists. Having grown up in an area of Northern California dominated by hippies, this was a breed of human I’d barely been exposed to. Where I’m from, capitalism is seen as evil and a system no “morally pure” person succeeds within.

This is obviously wrong, something I learned over the last year with every Zoom call I had with a kind capitalist. Cracks started to appear in the story I had been telling myself once I got to know successful entrepreneurs who seemed to not only be good people, but to be extra good actors, using their money to make more positive impact than they could have without it. My takeaway was that capitalism is extremely effective at giving action-oriented people with a vision for how the world could be better the resources they need to scale their ideas to become widely available. To put it simply, I became market-pilled by seeing the market work its magic right in front of me.

But it was the technologists themselves and their positive sum nature that I found myself most fascinated by. In contrast to zero-sum industries such as manufacturing that give capitalism a bad rap with their many negative externalities (namely emissions), it seemed to be a different, much more promising story for positive-sum industries like technology. Over time, I codified three ways of classifying the technologists I met by their actions and altruism — the throughline to all three archetypes being a shared enthusiasm for creative ideas, progress, and creating a better world. Through the process, I became obsessed with understanding the defining aspect of the successful entrepreneur — their commercial aptitude.

Part 1: Types of Technologists

Researchers. The people who come up with big ideas that push progress forward are often researchers. They’re non-commercial and satisfied with their contributions existing only in theory land. Researchers are instrumental at the beginning of a discipline’s creation but generally become less useful as the field matures and commercializes. Researchers are commonly found in academia, gain respect by writing and publishing their ideas, and usually make far better smart friends than they do venture investments. Researchers are often the biggest critics of the commercialization of their ideas — sometimes because they are thinking on longer timespans and other times because they are jealous of others profiting from their work. The best example of the researcher archetype is Alan Turing, one of the pioneers of (theoretical) computer science whose contributions include Turing machines, the Church-Turing thesis, the concept of undecidability, and the Turing test — all of which are still being applied to both research and commercial contexts to this day.

Hackers. These are non-commercial people who like making stuff. They’re executors and craftspeople — the creators of open-source projects who generally capture very little of the value that they create. Hackers are perfectly fine with this — for them, it’s much more about making the idea in their head real than it is about profiting from or growing it. Their technical skill makes them fully capable of building a thing that they materially benefit from, but they don’t want to scale the things they build because of how it changes the way they feel about the work (instead, they often make excellent founding engineers). This is why hackers can be one of the most frustrating archetypes to a venture investor — they’re so close to being a brilliant founder yet their inability or unwillingness to be commercial often limits what they build from ever reaching venture scale. The most infamous hackers are the ones whose anti-capitalist ideologies got them into trouble — namely Aaron Swartz, a co-founder of Reddit with a hacker heart who believed that everyone has a right to access publicly funded research and ultimately died from the consequences of that belief.

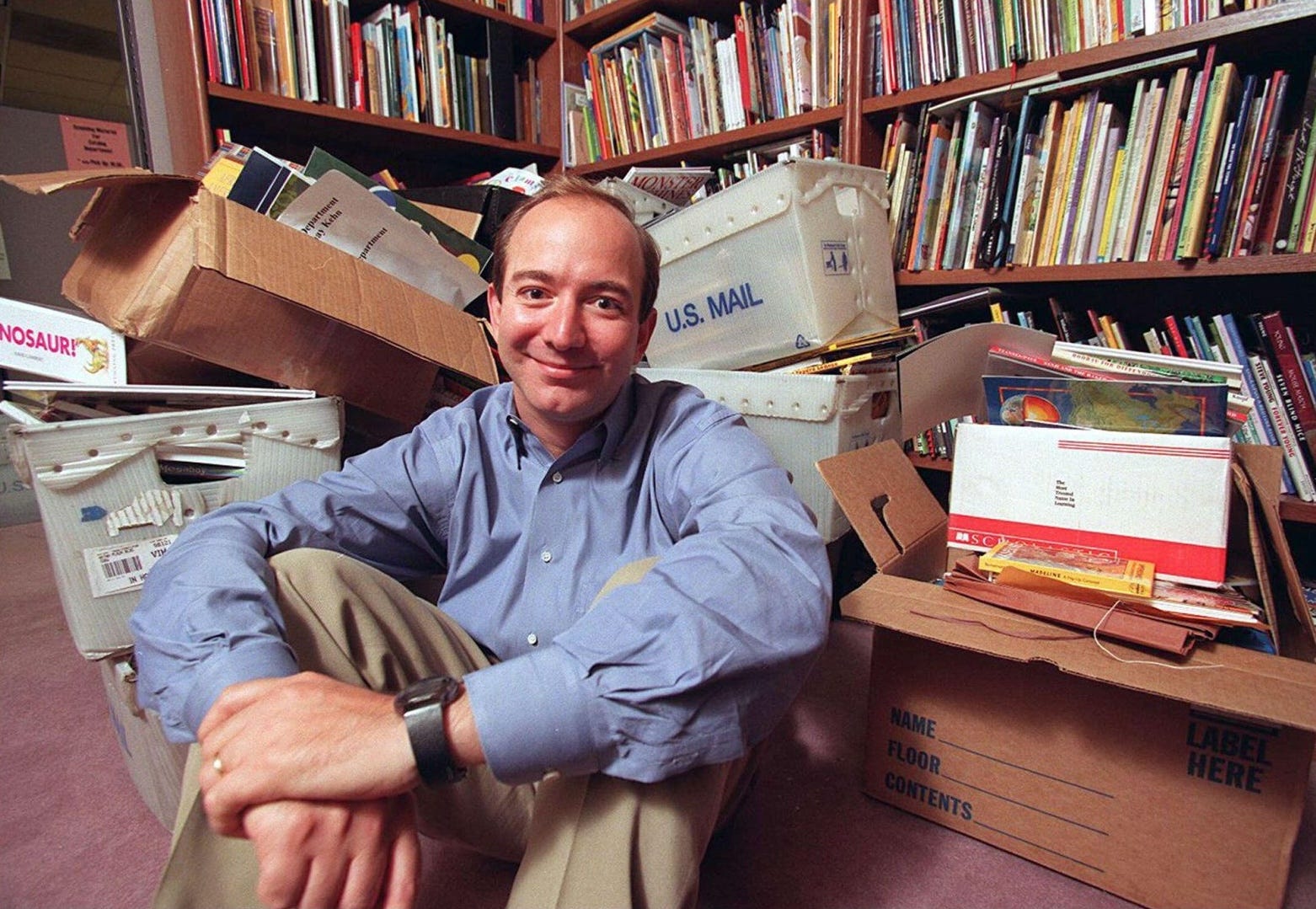

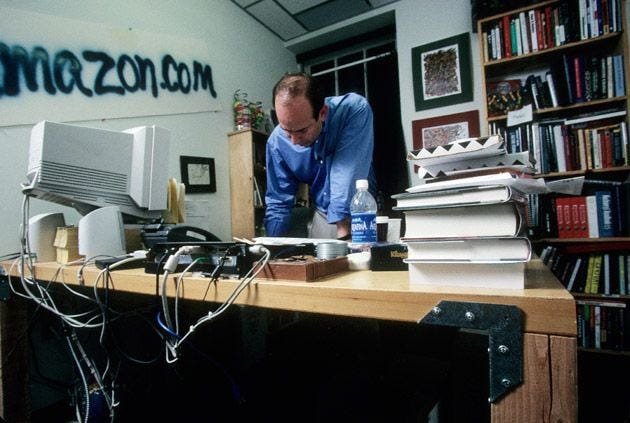

Entrepreneurs. The epitome of commerciality is embodied by the entrepreneur. They’re the weird, obsessive, extreme ones who always bias towards action and believe themselves to be outlier enough to win. Entrepreneurs shamelessly want to capture every bit of the value they create and usually believe that doing so will allow them to do even more for the people they’re serving and selling to. They’re the ones who are constantly guessing how much people would hypothetically pay for something and often know a weird amount about the companies they do business with. The best entrepreneurs are excellent at prioritizing what will make them the most money long-term and generally don’t get distracted by irrelevant details or intelligence games like jargon. Jeff Bezos is a great example of this archetype; Amazon has been explicitly hyper-commercial from the start by focusing solely on long-term growth and serving its customers.

Analyzing these archetypes and making calculated bets on where the money will be made is the job of the investor (and within technology, primarily the venture capitalist). Investors are separate from researchers, hackers, and entrepreneurs in that they are critical over creative — yet still share the commercial mindset of the entrepreneur. The work of the investor takes place mainly in their head since their only direct output is their decisions. These are the people who walk into a room and immediately size up square footage and deduce the margins of the business in question. They think about the world in terms of money and are frequently a little impatient. Investors have enough risk tolerance to put their money where their mouth is regarding what they think the future holds on the technological frontier, but not enough conviction to place a single bet on one idea. But at a baseline, they believe they want and deserve to win, unlike researchers and hackers. The investor mindset is best epitomized by Warren Buffet, who Alice Schroeder described as “able to see the essence of a business model as if you see an animal and he sees its DNA. He isn't interested in whether it's furry, all he sees is whether it can run and how well it will reproduce, the two key elements that determine whether its species will survive.”

Part 2: Zeroing in on the entrepreneurs

Understanding these archetypes is obviously important to venture capitalists. We need to keep tabs on the researchers for a peek into the future, recruit the hackers, and invest in the entrepreneurs. The more interesting question is: what mindset sets the successful entrepreneur apart?

I’d argue it’s chiefly a commercial one — generally developed through sheer experience starting and running businesses. Read the biographies of storied entrepreneurs and you’ll notice a theme: almost all of them learned to make money from an early age. Spending time in finance, being born into an entrepreneurial family, or joining an early-stage startup that gives you a lot of ownership and forces you to think like a business owner with a bottom line also seems to teach this skill. Commercial instincts are the result of exposure, perhaps even more than inherent talent.

The makeup of a successful entrepreneur is a special blend of wanting to make the world better and possessing enough commercial aptitude to figure out a way to do it in a successful and self-sustaining way. I’d argue that the most common motivator for commercial success is a strong desire for autonomy. The benefit of earning your own capital by founding a company is that it enables you to create something independent, lasting, and free from outside influences (in contrast to the reliance nonprofits and the public sector have on external entities).

Another more surface-level characteristic commonly found in successful entrepreneurs is that they’re voraciously curious and find great enjoyment in winning commercially. There’s a reason entrepreneurship at an early age is such a common pattern in those who win — the easiest time to get a taste for what winning feels like (and learn that losing isn’t so bad after all) is while your ego is least sensitive to failure. As people grow older, they’re less willing to try new things and often develop elaborate moral justifications to conceal the fact that they don’t think they’d be capable of making and selling something people want. A fear of failure seems to be the single most limiting factor to both entrepreneurial success and the creation of more entrepreneurs.

This begs the question though, why be commercial in the first place? Well, being commercial is what enables the entire capitalist system to exist. While I’m under no illusion that capitalism always creates good outcomes or successfully factors in all long-term considerations, I still believe it’s the best proven economic and political system we have to organize our society today.

I’ve noticed that most critiques of capitalism seem to be talking more about the product of human nature without any shared moral framework than the aforementioned system itself. Greed and capitalism are grouped together in our societal consciousness as synonymous despite the actuality being that greediness is an independent characteristic of human nature that will exist in any system humans are found. Positive-sum environments like technology are where capitalism shines, letting everyone win by turning something small into something big at breakneck speed.

Similarly, critiques of commerciality are more often about the aesthetics of the mentality than any real issue with its outcomes. As a society, we generally don’t find successful business people very sympathetic because they don’t share enough of themselves with the world for us to empathize. It’s also true that commercial instincts, taken to their extreme, can lead a person to behave too transactionally. Extremely commercial people often exude an air of wanting to take something from you, which no one likes.

But most people do want something from you — it’s just on what time scale. Their urgency is what dictates whether the experience will feel good or bad on the receiving end. After all, being transactional on the scale of a human lifetime is how most productive partnerships are structured. Long-term commercial instincts lead a person to think in a positive-sum way — surprisingly similar to the demeanor of capitalist-averse researchers and hackers. The difference is that those with commercial instincts don’t have a complicated relationship with winning within our economic system; they aren’t afraid of materially benefitting from their time and money investments. Warren Buffet said it best: “Success means being very patient, but aggressive when it's time.” It’s only through the prosperity produced by capitalism’s meritocracy that those who win like Buffet can (and do) give back towards causes they care about through philanthropy, strong redistributive tax mechanisms, etc.

At its core, being commercial is a mindset. At a bare minimum, you need to believe you deserve success — or at least, believe you are no less deserving than anyone else. Capitalism is designed to equip charismatic individuals who want to transform the world into a better place with the resources they need to do so. Whether the end they’re motivated by is power, fame, or faith, unabashedly capitalistic entrepreneurs know that wielding money as the tangible product of their work is the most effective means by which to actualize their impact at scale.

Special thanks to the very bright star that is Tara Seshan for clarifying convos and draft reads

Great piece!

Seems an important concept that successful entrepreneurs often combine a strong desire to win (including experiencing the fruits of their labor) while also having a moral compass, not treating business relationships too transactionally, and generally wanting to make the world a better place. Wish this nuance was covered more directly in entrepreneurial education (startup accelerators, business school, etc).

Great read!

More on entrepreneurs:

One entrepreneur has an inward expression of their autonomy. They become sales people and can commercialize their morals. They are the most independent because their charisma is transactional. They are the business model.

Others are are more outward and can build a research machine directed towards a frontier. Or hack together a company that feels good about their capital intentions. They are the ones leading the solving of our moral dilemmas and are the founders we recognize.