I’m talking to people and recording it! Some call this sort of thing a podcast. I’m calling mine Moth Minds and the premise is “interviews with high-agency humans.”

Upcoming interviews include guests such as: Josh Miller of Browser Company, Claire Hughes Johnson of Stripe, Akshay Kothari of Notion, and Joseph Cohen of Universe.

Subscribe to hear the latest on a weekly basis: Spotify, Apple, Google, Amazon, and Overcast.Highlights:

Questions to ask when evaluating a company: Does the research idea make sense as a good product? Will the person be a good leader and be able to recruit top talent? Does the market structure support the company in capturing the value it creates?

Investing your own money and building a competency that founders know you for is the best position to reap large-scale returns in venture

Building a company in a sleepy market that you deeply know is the easiest way to lower the cost of being a founder and make it more akin to being an investor

The least understood but most valuable moat is brand — being the first company to coin a new kind of interaction with your technology

We’re currently experiencing a lull and lack of progress in AI as shown by the incremental progress since GPT3 and the fact that OpenAI isn’t training GPT5

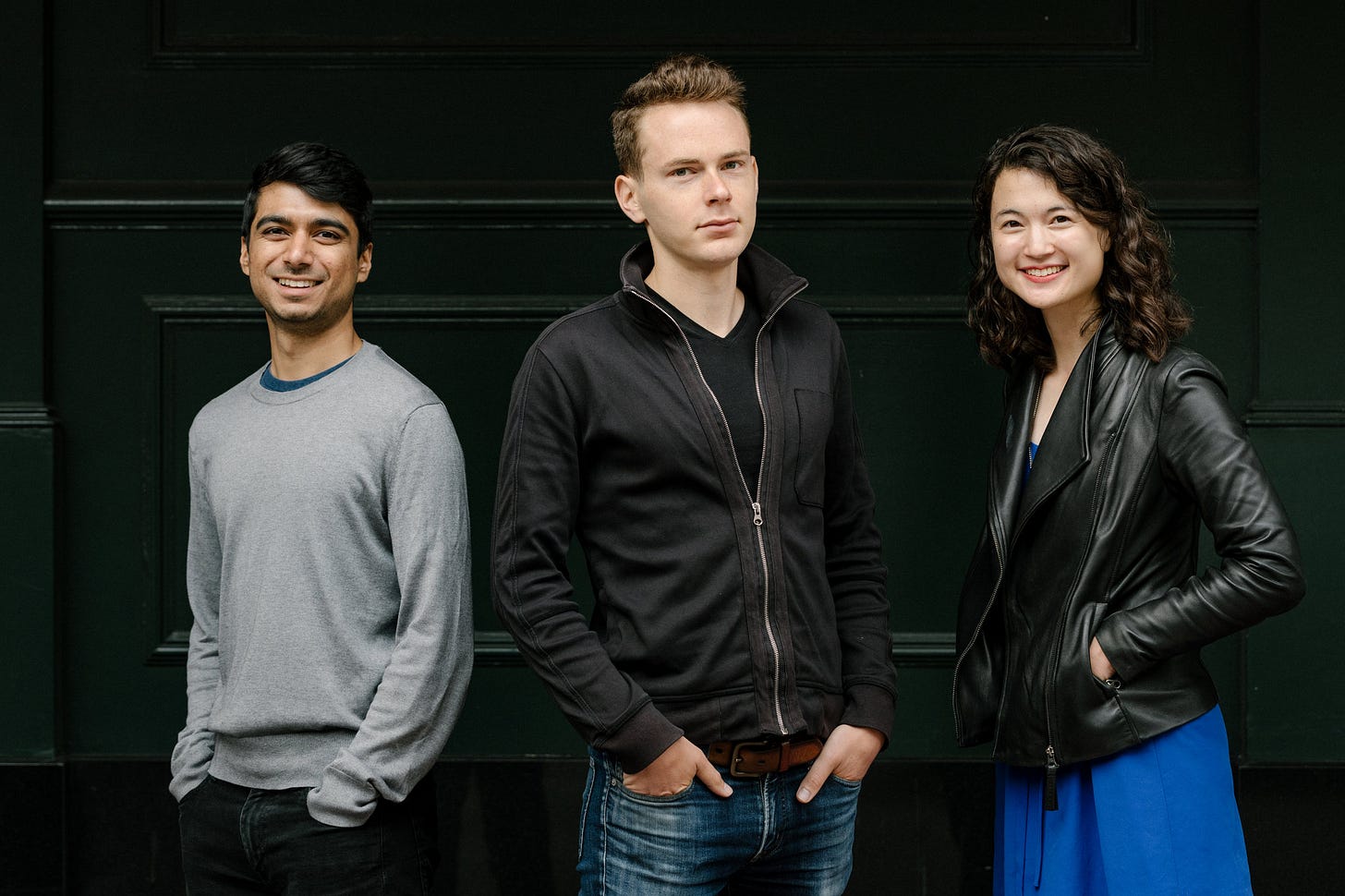

MM: Hey everybody. Today I'm joined by Daniel Gross, a prolific angel investor and entrepreneur. Daniel previously co-founded Cue, a search engine that was acquired by Apple. He then ran AI and search projects at Apple for four years, was a partner at Y Combinator, and founded the quantitative startup accelerator Pioneer — all while angel investing early in iconic startups like Figma, Uber, and Rippling along the way.

Our conversation covered Daniel’s thoughts on depth versus breadth of expertise, evaluating market versus founder, and how he thinks about the opportunities in AI. I hope you enjoy.

MM: Hello Daniel and welcome to the podcast.

DG: Thank you so much for having me.

MM: By way of introduction, my first question for you is, what is your moonshot these days?

DG: Well, first thanks for having me on. So I was born in Israel, in Jerusalem, Israel, which is not even the cool city of Israel that everyone talks about. It is not Tel Aviv. It's like telling people that you're from Kyoto, not Tokyo in Japan. So I'm sort of from a relatively obscure corner of the world. Managed to come to the US basically with nothing. I think I came to the United States with my bar mitzvah savings, not much more than that. And I come to California and start a company and have that company be acquired by Apple and have a pretty senior leadership position at Apple when I was pretty young. I was 18 when I moved to the US, 23 when I was running a bunch of machine learning stuff at Apple, and I'm 31 now. But that was obviously a very successful journey for me that I think I could have not done without the success of and the gifts of American dynamism and obviously the Silicon Valley system.

What's nice about the system that I had the opportunity to partake in is that the closest thing we have to am meritocracy, because the VCs in the industry are very much penalized for errors of omission, meaning missing the right company rather than ones of commission. So everyone's very eager to fund anyone that seems good. And it also is nice in the sense that no one's doing it philanthropically. People are doing it because they also want to make a return, which means you can attract the best kinds of talent to work on this particular thing. Anyway, long story short, VC sort of worked out for me personally as a founder, and I obviously want to make it work now for other people, both as someone who invests but also for a financial return, but also very much wants to see if I can change lives for the better.

And so that's sort of my vague moonshot. I don't have a Mars thing or whatever and I can probably wax poetic about AI and all that jazz, but underlying all of that is I by no means made it. I definitely have sleepless nights, things I'm working on all that sort of stuff, but I'm in a much better position than I was when I first started and I do get joy out of paying that forward to other people. So that's sort of where I am right now in my life. I think maybe I'd start another company in the future, maybe not. But right now I'm enjoying this science/art of finding and funding people that go on to create great things. So that's my moonshot, although it takes place on Earth

Given your skillsets, resources, and where you are now, how have you honed in on how you could have the biggest impact and decided to spend your time?

DG: I regretfully have not been good at optimizing where I spend my time based on where I can have the most leverage. That has been an issue I've had I think since I was 12 that has frustrated many teachers at school, but I somehow managed to pull it through. I tend to spend a lot of time and I tend to have the blessing that I have a career that lets me do that and in fact rewards me for that. Just really going down various rabbit holes that are interesting to me, I tend to be a pretty commercial person at heart, so I tend to not really go too far down theoretical rabbit holes that don't have some commercial return. When you add those two things together, the role of allocating capital is a pretty good one because you will meet someone working on some type of cutting-edge research idea and then you usually have something like 72 hours to figure out three things.

Does the research idea make sense in terms of it potentially becoming a good product? Will the person be a good leader of people and be able to recruit top talent to work for them? And then third, I think probably most importantly, does the market structure support this kind of thing existing in the world where the company captures the value it creates? So you have to figure that out quickly and then you make a decision. But those three things, figuring out a product, the founded market, do require the ability and desire to just go from very little knowledge to a lot of knowledge about something fairly quickly.

“1) Does the research idea make sense in terms of it potentially becoming a good product?

2) Will the person be a good leader of people and be able to recruit top talent to work for them?

3) Does the market structure support this kind of thing existing in the world where the company captures the value it creates?”

So I enjoy doing that. I've been doing that my whole life and that's what I gravitate normally too. Not everyone gravitates to this. Some people really don't like the uncertainty of the job. Some people really don't like the fact that you don't actually build depth. And it is something that irks me occasionally. If you start a company, you do get to build depth, but you get to build breadth and so you get to have a sense of what, say, every single decent AI company is doing is something I think I have a modest index on. Definitely not the best, but I like doing that sort of thing and it's some innate part of me I think enjoys doing it. But it's probably not the most efficient thing.

I've often wondered that. If I were placing me to maximize the productive economic output of a nation, I don't know exactly. I can make the case of course that I put myself where I am just so I'd feel good about it. But there's probably are better thing. Probably is a me that is focused on applying that same sort of have a lot of ideas, try a lot of different things, but to sell cultures. And that's probably a scientist version of me that I'm definitely not going to be. So I don't know if it's the most productive on depending on what scale of productive you mean, but it is where I am. So I'm pretty happy with how it is turning out so far.

MM: Yeah. What do you think you can uniquely do with breadth over depth? Is it being able to discern what makes sense in a sea of so much noise or what are some other examples that come to mind?

DG: One of the advantages you get is you tend to pattern recognize and you tend to see a lot of different things. It will often be the case that you get one pitch of one particular idea and you think it's novel and then literally in the same week, you're pitched that same thing two, three other times by different teams. So you're then able to sort of say, "Well that's interesting. There's a lot of people working on this. How should that change my decision about how the market structure will turn out?" Because for example, if everyone's going to work on it and it's one of these things where it's very easy for a 23-year old MIT kid to do, then that usually will end up as a Git Repo and not a company. So that's super helpful. It's the thing you can do when you have breadth.

This is, I guess, breadth in people that I meet, not necessarily breadth in industries, we'll get to that in a second. But identifying basically the future market structure and future margin structure of businesses is one thing you can do. Patterns are also good just in terms of what's working and what's not working for people. You get this at later stage when you speak to companies at B and C phases, you tend to identify a common thing. For example, companies that resell enrichment data, all of those platforms, won't name them cause it's a bit of a pejorative, but they tend to tap out in terms of revenue at a certain size or scale. You learn that after you've seen that story unfold over and over. Industry breadth is super useful too because it helps you actually figure out the underlying personalities of founders that work really well regardless of the industry that you're in.

And you will often see this sort of same story of a person who could be starting a new type of enterprise, SaaS company, or could be starting a biotech lab or something in physics or some kind of AI thing. And because you see people across disciplines succeed, you're sometimes able to zero out and mask out the industry and really focus on what seems like a really good kind of person to invest in. I think it's actually very helpful to see industry variety in that sense. But there's disadvantages to it too. There are limits to what you can learn about a particular industry. And I do think the other much bigger thing is I am very careful in general, and in any act of trade to make sure that the selection effects that got the trade back to me and to my inbox are good.

The counterparty is very important, and if you are very wide and you're not careful, you can end up in situations where you don't have great selection effects because you went for breath and so you did some kind of biotech deal. And you didn't ask the question of, "Why did I see this biotech deal? Why didn't a biotech professional see it?" Whereas if you have depth, you're much better at that. So I do think you have to be a little bit careful there because that stuff really matters. I actually think that's probably the number one thing in venture VCs don't pay attention to, people who trade assets in general. If you talk to anyone that trades bonds, they will tell you the counterparty matters a lot. In fact, it's the largest piece of information they get. I think venture, people pay almost zero attention to that about why is this deal coming to me? And I think it matters a ton.

There's a ton of embedded information in, why did this particular company, why did that person introduce me to this company and not introduce someone else? Who else was introduced? Who else said no? Some situations that you have the confidence, be it the stage of the business or the industry that the business is in to know that you're going to have a positive selection effect, sometimes the business is acutely distressed and so everyone actually did say no for obvious reasons and you see something there that others didn't. But if you don't have good answers to those questions that... I mean I at least have run away from situations where that's the case.

“There's a ton of embedded information in why this person introduced me to this company and didn’t introduce someone else. Who else said no?”

MM: Yeah. That makes a lot of sense. Interesting. It reminds me too of the concept of staying top of mind and I think that it does dictate some things, but it's not necessarily good things. You might just be served the stuff that people are trying to get rid of and out of their inbox.

DG: I think there's a really interesting question of what causes someone to think about you. And you're right that there's a dumb recency answer to that question. If you're out there marketing yourself a lot, then people will just think about you. There're deeper things. I probably have fallen prey to this just because of my natural proclivities are a little bit technical, but I do tend to be technical heavy in the people that pitch me, which is fine. I mean that's sort of who I am, but that's because people, when they have a meaty technical problem, think DG will probably fund this. It's good to have a model of mind basically for why the counterparty is reaching out to you and how they model you, and are you the first person in their sell process or the last?

MM: Totally. What do you think has been your angel-investing superpower?

DG: I don't know that I have a superpower, but I think, look, the honest truth that no one wants to admit about venture is there's a really ridiculous amount of luck in it. And I often think it's, don't about it too much because it's pretty nihilistic if you think about it. Venture, a disproportionate amount of success, not for I think just me, but for many people is luck. Because when you have power law outcomes that are usually occurring after large market shifts, there's so much that is just not captured in the data of whatever regression model you want to build that you're just going to have to ascribe it to luck. And you know how you got there, right place, right time, and that's a big faction of it. But that's a bit of a dodge answer.

One of the things I've gotten better at, and I'm still learning this sport every day, is a need to understand when a company comes to your doorstep or you reach out to them and you meet them, I think people who have been operators who started a business, they tend to invest in that asset as if they were running it. And it's a beautiful mistake. It comes out of an abundance of optimism. You tend to think, "Boy, this is a great concept. If I were running it, I would do A and B and C." And that doesn't work. You need to invest in what's in front of you and what the market has provided in front of you.

“I think people who have been operators who started a business, they tend to invest in that asset as if they were running it. And it's a beautiful mistake… You tend to think, ‘Boy, this is a great concept. If I were running it, I would do A and B and C.’ And that doesn't work.”

So one thing I've definitely gotten better at is sort of realizing that, and definitely took a few cohorts for me to realize that. Then it becomes much more about you get some data points from meeting the person. Maybe you spend 30, 60, 90 minutes with them off 1, 2, 3 interactions and you now need to build a mental model for giving them 1 million decisions that actor will make over the course of their company in the next 3 to 10 years. What are they going to make the marginal decision for or to do?

And that's really the art part of this. I think the market structure forecasting is a little bit more of a science, it's a bit easier to do, but the art part is doing that. And there's a very natural way to get better at it. Once you meet a large enough bank of people, you can... High failure rates that you're penalized for. So you're super paranoid about predicting the wrong thing, but you can make some kind of guesstimate about what's going to happen. Combined with some type of market guesstimate, I think you can make a pretty decent bet. And again, all of these things are probabilities, and you try to make more than one investment obviously so that you can afford some kind of failure rate, but really make sure you don't miss the winners. I think venture's very unique in that way, in a way that almost every other asset class is not.

I think as we think of where we sit in the broader realm of all the money things, we are the riskiest, and so we're really paid to take on risk, which means we really can't miss things. So I say all this, and I already in my head I can hear the other people saying, "Well, what about all sorts of biases and whatnot?" And I'd say the great thing about ventures, there's this massive financial incentive not to make mistakes on that particular axis.

But anyway, that's the thing you get better at, you meet more people and then you tend to be able to build a better and better model of folks. When I was just getting started, I basically got a bunch of cash from Apple and I pay taxes to the US government and then I started investing with that money, and I remember having a similar debate with myself. Maybe I know what me looks like, but I don't want to invest in people that sell to Apple. I want to invest in people that go public. And so I don't really know what that looks like enough. Of course, I was a YC founder and so I knew a bunch of YC people and that was super helpful. But I remember watching on YouTube, the early interviews of Mark Zuckerberg and Larry Ellison and Steve just trying to get in my head the photons of charisma. Maybe that was helpful too.

MM: That's super interesting. What were the commonalities that you pulled out from those interviews?

DG: I don't know. These are things like a black box model, it's a little hard for me to put it into words and transmit those words in a way where you'll be able to interpret it. I think it's just good to do. I still don't know if it works over video. I mean, I find it's sort of an interesting aside, but something about the transmission and memory and learning over video on a 2D plane was very different from 3D in person. But anyway, I hope it was somewhat useful because I think I have watched every video in the every Steve Jobs video YouTube channel back when it existed. I think it's good to just meet people, and I would always keep track of things I passed on and omission mistakes. Those battle scars are useful.

The good news is I don't think venture is that hard if the broader macroeconomic wins are in your favor. I think maybe another thing venture people tend to underestimate, or not pay enough attention to, is the broader economy. I think people are paying a little bit more attention to it now for the first time in 12 to 13 years because the economy, it's like mother yeast or whatever of the whole kombucha, started malfunctioning. So people are like, oh, and now everyone has opinions about interest rates and stuff like that. Rest assured, no one was talking about that throughout the entirety of 2021 except maybe one or two. I mean Keith Rabois very famously called the market top to the week. The only people who thought that way in my view were people that were either financial meatheads, maybe like me or people that had gone through 2000 and remembered what it's like. And so now I think more and more people realize this, but it's exceptionally true.

You could have the finial typical gifts of the best VC if you're in the first part of the 1970s, doesn't matter. It's just not a good time. And of course if you started in the 1970s, fantastic time. I believe that's exactly when Sequoia Capital started. I think their first investment was Atari and I think the second was Apple. But that whole story, that whole investing, VC talent selection, whatever, none of that matters if the economy is not growing. So ultimately, I think we're surfing these waves more than we make them and it's good people realize that now, but I think it's a humbling thing to realize. Even this tech AI thing that's going on now and people have all sorts of big projections about how it's a bigger deal than the internet. It's a bigger deal than fire. It's a bigger deal than the wheel.

The truth is these companies will struggle, for example, if the risk-free interest rates go up to 7, 8, 9, 10%, that means the borrowing cost for every single one of these companies, for every single one of the GPU hyperscalers that make GPUs will skyrocket, which means the GPUs will be much more expensive, which means the companies will be able to use much less of them, which means all of this AI progress will happen, it'll just happen much slower. So I think we are ultimately players in a much larger field. Maybe it's the best part of the field to play in.

MM: What do you think are the unique opportunities right now because of the macro?

DG: Oh, because of the macro, I don't know the macro thing. There's a Dunning-Kruger effect with macro and it's really important to eclipse the Dunning-Kruger peak, the Dunning-Kruger Zenith and be in the Dunning-Kruger collapse with macro, which I am thankfully. Not enough people have gone that far. So I highly encourage everyone to make your macro trades and get them wrong so you finally realize no one knows how this works. To be fair, I do think there are some people that are extremely good at knowing how it works. I do think that is a full-time job. So I don't know how to predict the macro thing. So you might say, "Wait a minute, DG, you said you have to be investing in a good cohort, so how do you make sure you're doing that?" And this is more of a spiritual wish of mine, meaning I don't think it's super actionable and I think if the economy tanks, everyone loses.

Yeah, I don't think shorting actually works at scale and definitely not in our industry. So you have to pray things work out and the world continues to expand and the economies continue to expand and things continue to grow. So I don't know how to make macro articulations. And anyone that's overconfident about this stuff, unless they are Stan Druckenmiller, should be able to pull out a track record that shows five estates and three planes they bought came out of that overconfidence in macro. Otherwise, I would just have to say shut up.

MM: Great answer.

DG: But I don't know. I think there are things that are exciting in the field of technology. I know a little bit about that field and obviously maybe the interesting question is, what is exciting outside of the world of AI? Because it's very easy to wax poetic about how exciting that is.

And the truth is, I think there's a lot of pieces of software that are still being built now in the world of enterprise SaaS and mobile that are just getting better and better. I have no economic interest in Nostr, whatever that Twitter clone is that Jack Dorsey made, but it is a phenomenon now that I see people using. We can talk about AI all day, but there are things happening outside of AI that are exciting and big. But it's the world economy that pulls back because people get super afraid or people handed out loans to the wrong people and they default on them, then everyone's going to have to have a hangover. That's not a selective thing.

MM: Yeah. How do you compare the ideal risk profile of an investor versus a founder?

DG: I think the degrees of reputational risk and ego risk are similar. Meaning maybe there's three classes of people, if I can stratify it. I would say that there are founders, there are people investing their own money and then there are professional investors investing other people's money. I think the best category to be in is definitely investing your own money because I have definitely had very large personal wins I didn't have to tell anyone about and also have had very large personal write-offs I didn't have to tell anyone about. So that's like a bit demoralizing, but that's okay. At the end of the day, it's okay. I think when you run a firm and you're doing things on behalf of other people, of course there's that inner monologue whether you're a founder or a professional investor and you're thinking, "Oh, it's going to be super embarrassing if that happened."

And maybe that's a good thing by the way, because it drives the marginal performance. I definitely think for the cohorts I've invested, maybe I would've been better if earlier on I would've become more professionalized. I obviously think, look, if you just look at the financial risk, of course founders carry much more of that just because as an investor you basically get to invest money as a founder, you get to invest time and so because you cannot clone yourself, you are focused on one example of the high risk assets. Theoretically as an investor, you build a portfolio and so you get to duplicate that. And of course you own a little bit less of every single one thing, but again, everyone's searching for the thousand X outcomes, so maybe that doesn't really matter. So yeah, I think a founder is much more risky of an activity, but investors still carry that same sleepless night dynamic just because you're stewards of someone else and you told that other person a whole story and you got to keep that story going.

I think that all is a good thing at the limit. Conscientiousness is like cortisol. Too much of it, you have Cushing's, too little that you have Addison syndrome, so you sort of need the right amount. It's a U-shaped curve. Now maybe an interesting question, as a founder, how can you have the lowest amount of risk that would make it more akin to being an investor? And I do think there's a story of going after a sleepy market that you really know that is a very low risk strategy that not enough people pursue because they don't know that sleepy market. Usually the next question that comes up when you tell people to do this is, how do I find that sleepy market? And usually you give them some vague hand-wavy thing, you should just go email a lot of people and go intern at some energy company in Texas for a while and come back when you figure out what SaaS you can sell them.

“As a founder, how can you have the lowest amount of risk that would make it more akin to being an investor? I do think there's a story of going after a sleepy market that you really know.”

No one actually does that. I mean, there are probably people that do that. Unfortunately, not enough of them have emailed me and so I don't get to go on the journey with them. But I've seen people execute this pretty well and it's actually not that complicated. And you see shades of this too in this Cisco spin in and spin out where you have people that have literally four times throughout their life left, started the same networking company, had it get acquired by Cisco, spent some time at Cisco, left, started the same networking company. So there are modes of it that are de-risked. People don't like going after those, precisely because, or don't know how to go after them because they're less competitive. And they're less competitive because they don't satisfy that immediate sense that your phenotypical, whatever, a 25-year-old founder has that it'll be really big or really successful.

That's why you tend to always be overweighted, people that are making a LangChain competitor, an underweighted, someone that is making software for helicopter pilots that fly to oil rigs. I just made that up. But I don't know, maybe that's the thing. I think that's a huge skill for someone that's willing to do the slap. And earlier we said maybe something about the investors paying a lot of attention to the counterparty risk and why you're getting the deal that you're shown. I think the equivalent that for founders is competition risk. Peter Thiel very famously said this in his book, "Competition is for losers." And I think that's a bit defeatist to be honest. The truth is real winners are in competitive fields and just win them. So it's not true at all. But there definitely is a class of winner that just went after an uncompetitive field, and I think that person is not celebrated, or that's not attempted enough.

So I think about that a lot as a founder. It doesn't matter by the way, what we say on this podcast because no one ambitious enough will listen because everyone ambitious enough I think has an innate sense of belief. So I've learned this sort of advice. You can only watch as people's eyes gloss over when you tell it to them and you realize they're not going to follow single... Anyway, so the world continues and the cycle continues and you get more and more people. It's really amazing to see, literally jumping off a cliff after staring down and seeing there's just loads of bodies down there. They're just jumping off. That's okay because unlike with your physical body, companies can die and people remain alive and learn a lot and try again. And it is often the case that when you see a second or third time founder, they're like, "Okay, I'm definitely not doing that hyper-competitive thing. That seems cool, but everyone else is doing it now."

MM: Yep. It's interesting too because it seems like it's low status to go after fields that are not competitive and not nearly as shiny. And I wonder what would make that different. How does a field that is unsexy in nature become attractive and celebrated as something to win in? I don't know if you have any thoughts on that, but it seems like a eternal conundrum.

DG: Well, you usually have a winner and usually the winner is even just they raised a lot at the series B. And people are like, "Wait a minute, I can do that too." And then the market is much more reflexive I think than anyone gives a credit for. One of the great lines of our time is the efficient market hypothesis. It's definitely not efficient, and people are mimetic and there's a whole lemming mentality everywhere. So that does actually leave massive pockets of gold just lying on the street for anyone who wants to think for themselves and pick it up. So you tend to basically have these things get ignored until there's a big noisy round and then that attracts competitors and you have to hope if you're the apex predator that went after the super competitive market, that your product is so darn good that you make it extremely unappetizing.

Not for the founder, you're not going to do that, but for the venture capital community, not willing to invest in you and arm you with their stuff. And a good example of that that I think we're seeing today, spoken AI itself. And I do think there was a window in time where the venture capital community had a lot of appetite to fund these other AI labs that were not directly commercial, but we're working on AGI in some vague and unsatisfying way. My sense is that appetite has dried up in the venture capital world and it has spread out to further a field concentric circles of money. So those people are pitching sovereign wealth funds. Those people are pitching random family offices.

I know this, because I usually get a reference call about that sort of stuff. But I think had GPT4 not been demonstrably better than Cohere's models, as an example. And I say this is someone who loves Cohere's and very much hopes they catch up, we benefit all from competition, then maybe the reality would've been different. But anyway, the much better life in my view is to build a great company in a sleepy market. You don't have to get on Twitter every hour. You can just have your own thing and have great five close friends and family and then a little ranch somewhere and that's it. That's a great life.

“The much better life in my view is to build a great company in a sleepy market. You don't have to get on Twitter every hour. You can just have your own thing and have five great close friends and family and a little ranch somewhere and that's it.”

MM: That's great. Drilling a little bit deeper into your thoughts on AI, I am curious wearing your VC hat, what are the qualities of the companies that you think will be enduring?

DG: Well in 2018, 2017, 2016, you sort of would sit there and you take these meetings and you would basically have a massive overdose of extroversion, meaning you'd get these MBA, super happy, healthy people have no problem getting on a United flight every day with a stop-over to go sell some products somewhere. They love the lounge, food, all that stuff, but they didn't know how to code. And so the challenge was everyone needed a "coder," which is a pejorative term in my view. It's talking about software engineers like they're monkeys. But that was the thing. I need a coder. Flash forward, at least from my little vantage point from the people who email me, I think we have the opposite problem, meaning you have these brilliant scientists who are sensitive and are not getting a United flight every day with a stop-over to go sell their product.

They want to make something from their keyboard, from their air-conditioned, temperature-controlled home that does fantastic miracles to be honest. But those people don't want to do sales, they don't want to do go-to-market. They sort of expect the product to come to them. We've now shifted to the other end of the equilibrium. We have too many introverts. And that's okay. I mean that's what happens when there's a new frontier field. I remember when the iPhone came out, '07, and I think apps were came out '08, '09, if memory serves. There were basically no good objective C engineers. It was just like a bunch of the Mac engineer guys who had been at it for 10 years selling to an audience of no users, and they were sort of esteets. So you got your first iPhone apps were basically not commercial.

It took a while until Uber and Instacart got their act together. Now of course, making an iPhone app's a total joke, relatively speaking, React Native and all that jazz. So I think we're in this field where because it's frontier, you tend to get a lot of brilliant scientists, a lot of Steve Wozniak, not enough Steve Jobs. There are a few people that have both, those who have always been rare historically. I don't even think Steve Jobs had both. I mean he's always been surrounded by technical brilliant people.

\Weirdly, I think Larry Ellison is a very good example of someone, who back in his day had both, but the best founders tend to be able to breeze in about a pie torch library, but ultimately really want commercial success and really willing to fight for it. You see that in their companies too. So in my view, the only people that actually have generated either eyeballs or dollars, which are the only two things that matter in my view in business, in tech business from AI, are people that do have their own models.

They're not using something off the shelf, but they are ultimately in service of a physical product that they're selling to customers. So obviously ChatGPT is the most notable example. This could be a publicly traded company in terms of the revenue it's making now. Midjourney is another example of that. Lexica's another example of that. Character.ai is another example of that. The fact that they're building their own models a little nice, actually from a margin perspective's a bit of a bummer. But I think the main thing is that they're building a product that makes sense.

Now, small sidebar on the whole enterprise AI thing, which is a very popular pitch. I think the main question you got to ask yourself when you meet the enterprise AI company number 1001 is clearly it's a huge opportunity. Basically the electrical grid has been invented and the homes aren't plugged in.

Fortune 500 is just not connected to AI. But you got to think about the phenotypes of people that are going to be really good at doing that and the underlying market structure of how those companies will evolve since AI means something different to every single company, sort of not like a database or a payment solution where you could just sell that concept to a CIO, people understand we're using this as our gateway now and we should switch to that because AI is this sort of amorphous glue. It's like maple syrup and it creates its own shapes and every different company. Then you sort of need this someone to build a bespoke product and a system of integrators and have those integrators sell the thing to the business. And does that person, will they build and manage that team? Do they even want to do that? Or they just want to tinker with their model and have it do little cool summaries?

So that's the issue with enterprise AI. Occasionally you come across founders that have those phenotypes, like the Distill guy is pretty good, but more often than not, they really only have Wozniak without Steve Jobs. I think you have to find someone that you know is inherently commercial. And I've made this case now and think ServiceNow is an amazing thing to go look at. If you're a founder and you want to do enterprise AI, go to the ServiceNow website. Summarize what ServiceNow actually does after reading their website. I guarantee you, it's going to take a couple cycles to figure that out. And that translational energy of going from it's a bunch of Google forms to servicenow.com, I think, which is a hundred billion dollar company, is what's missing in a lot of the enterprise AI space.

By the way, for every day where that's the person that's going to mop it up a little bit too late, a little bit too badly, but with the right customer base and sales channel dynamics is Microsoft. So I think the world is the oyster of the founder for the taking, but they have to act now. You know damn sure, every CEO, every Fortune 500 CEO needs an AI thing they can say in their next earning call. But you also know damn sure that the CEOs of Microsoft and Box and Dropbox and Accenture, they're all working to provide that solution.

Just to connect all these dots, what I would say is this is where you go with the sleepy industry. And you hit them up and you say, "I will provide the AI for you," or whatever that means. So you end up doing, well, I don't know what it's going to be and you may have to get your hands dirty and actually go travel somewhere and literally get your hands dirty and sell to John Deere. But that again, I think that's a super lucrative area.

One final thing I'd say is we have seen the businesses that have product market fit in AI have gone from no revenue to tens in some cases hundreds of millions of ARR extremely quickly. In fact, so quickly that I always wonder, it's like an unhealthy kind of growth, but there's real thirst for it. In that sense, I think this revolution is extremely different from pretty much all the past technology waves for different reasons. It's different from crypto in my view. And I say this not as someone who's super well studied in crypto, but real eyeballs are being spent. Hours a day people are talking to characters on Character and ChatGPT. And then it's different from mobile and from the web and the right of adoption, which is a byproduct of not necessarily AI, but the interconnectivity of the whole world, meaning the same dynamic that drives the SVB bank run and the First Republic bank run is the dynamic that catapults ChatGPT to hundreds of millions of ARR because everyone's fully connected.

So these wildfires, good or bad, spread really quickly. So that's the opportunity now is you sort of know that the wildfires spread really quickly and you want to be the company that fills that box. Cause once you're there, it's harder to compete with you. I say this as someone who is a great admirer of Character, but when people think of talking to the AI thing, it's ChatGPT, it's chat.openai.com. That's ultimately the real moat in my view.

Everyone's like, "Oh, it's the data moat. It's the capital moat. It's the Microsoft." No, in my view, the moat is what it always has been. Even I think in the case of Uber, oh, it's a network effect that the drivers, no. The moat is that when people want to go somewhere, they think of the Uber app. I think that's a huge, huge deal and tends to get undervalued because it's like not intellectually appreciated in a world and in a city where people mostly drive Prius's and wear hoodies, no one wants to think of the aesthetics of a brand moat, but I think that's a huge deal.

“The moat is that when people want to go somewhere, they think of the Uber app. I think that's a huge deal and tends to get undervalued because… no one wants to think of the aesthetics of a brand moat.”

So the opportunity on the consumer side is to become the brand for a new kind of interaction or thing. And I think the opportunity on the enterprise side is to find a sleepy market and just really satisfy those people. In the whole alpha of the company, in that letter example is that it's so sleepy and boring and to your point, low status, you're not going to get a lot of competition, which is awesome.

MM: Do you think that the wildfire dynamic plays into when you're tackling a sleepy market, or is that more something to popularize the technology itself or attract talent?

DG: Well, this idea that things move really quickly, it's a good example for when things go south, when people withdraw their money from a bank because of the reflexive effect of the bank stock going down, which drives more people to short it, which drives more people to withdraw money. Then as we found out, the bank does become worthless. So that's the self-fulfilling prophecy narrative in the bad way. In the positive way, in the consumer world in particular, is how I would answer your question. I think it applies really quickly just because everything's really connected and people have credit cards ready to go. They have cash. Enough people have cash.

I think I agree with what you're saying. In the enterprise world, the degree of speed and tempo, especially in a sleepy market might be a bit slower and you won't get that effect of you got really big on Twitter and so you managed to raise a $250 million round, but you will instead get people that won't have the flip side of the benefit of what we just described in consumers, which is they won't churn off you when there's a new hot person in town.

MM: Right. Yeah.

DG: Which I think if you do not become embedded in the skull of your users as the thing for the thing, people will churn off in my view. So that's the issue with it's just brand. It only works when you really become the brand. And you could argue the jury is still out. I mean, I think one thing people will rediscover from the search engine wars is in this race to become the place people want to go to and visit. This just feels like it'll satisfy your request. Speed is actually I think a supremely underrated factor because I think when people have a really good experience with something in general, it just is more likely to bind on their minds to the place to go for that sort of thing. Speed is just a fairly cheap way to make something really good.

Obviously having it to satisfy the request is really good, but just having a sense of tempo and liveliness is I think super important. We see that this OpenAI, it was very clever and smart to release streaming. When you think of an interaction, especially now with GPT3.5, it's fast, which is important. And Bard, I was really surprised at the end of the day. It's really fascinating. There's a company that was built on the preconception that speed matters. I mean the thing Google always had that made everyone jealous who was building a different search engine was they were like 200, 300 MS around the world. They were always fast. And the reason the culture needed to do that is they would have all these ab tests that would show if they were 600 MS, you would run less queries and then be less likely to click on an ad.

So it's mind-boggling to me that culture and that company ultimately produced Bard, which is an assistant that doesn't stream its tokens. And so if you ask Bard, you'll see it's actually pretty fast, but the end result is held and so it actually feels slow. To me, it's sort of a damning sign of Google culture. I really don't know what's going on in there. And it's probably, like many great acts of history, going to depend on the health vim and vigor of the four or five people. In Google's case, I think it would be the founders.

MM: One last question for you is where do you disagree with your peers on AI?

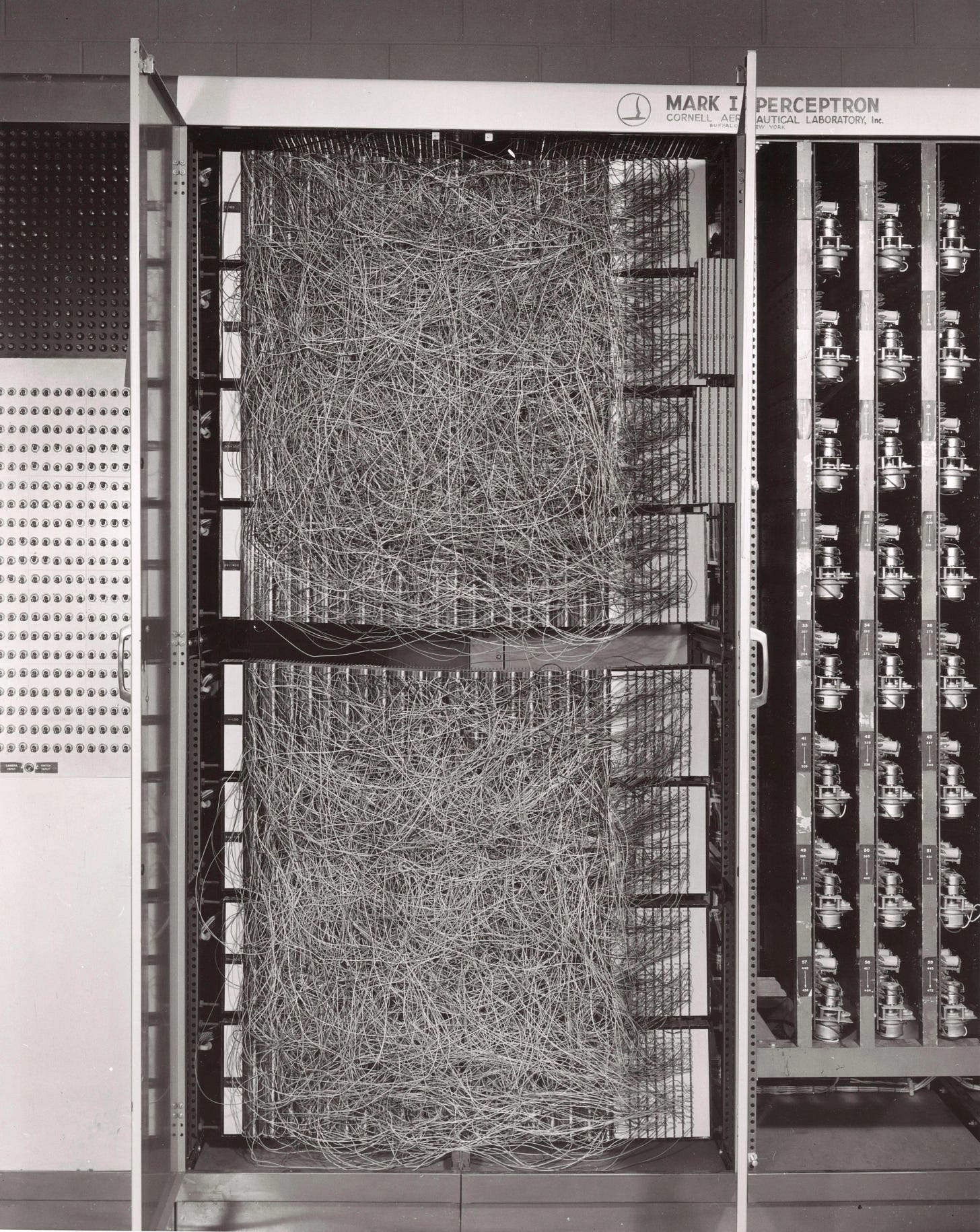

DG: It's tough. I'm gifted in having peers that have not just a variety of opinions, but ever-changing opinions. I mean, maybe the AI is sort of a special field. It's very alive. It's not like the field of archeology or whatever that just doesn't change that often. If we take the broader term of my peers' industry at large, in my view actually right now we're in a bit of a lull, and I don't think this is the industry view, meaning I don't think progress is accelerating anymore. My contention would be that GPT3 came out basically 2+ years ago and the leap between 2 to 3 was nothing like the leap between 3 and 4. So basically the big leap happened over two years ago. My contention would be that everything that's happened since is fairly incremental and we have heard from OpenAI that they're not training GBT5.

“In my view right now we're in a bit of a lull [in AI]… meaning I don't think progress is accelerating anymore. My contention would be that GPT3 came out basically 2+ years ago and the leap between 2 to 3 was nothing like the leap between 3 and 4… My contention would be that everything that's happened since is fairly incremental and we’ve heard from OpenAI that they're not training GPT5.”

So if we think of the main distinction between GPT3 and GPT4, as a consumer, I only see it really be better at coding. In terms of day-to-day usage and needs, we could argue ad nauseum about benchmarks, but it's better at coding. Now I think it's better at coding because it got shown a lot of specialized coding data like how to code well by lots of grad students, which all makes sense. I mean, if you look at the way it codes, it's not exactly the final output that exists on the internet. On GitHub, the largest improvement has just been through more fine-tuning, which means the returns to scale or diminishing slash we're not scaling really anymore. I do think in the next one day to 12 months, there'll be another miracle where the context windows will grow drastically. That seems pretty straightforward to do. If I had to implement it in the next hour, I could, but I think that'll happen.

But I don't know that progress is accelerating at all, meaning I think it's been fairly static. And it makes sense. We will go through winters, summers, falls, and springs. Not every month is going to look like that month where everything seems to happen every single day. But that would be my contention. And I don't think a lot of people would agree because if you go on Twitter, there's all these demos. But I say this is someone who's tried all the demos I can possibly try. There's a lot of, to use the proper collegiate term, misinformation on Twitter in that a lot of the demos just don't work and are really good demos. I think anyone that's really used some of the stuff would know that at the end of the day, once GPT falls down this mistake of making code that doesn't execute, the odds of you showing the subsequent failures to GPT and it magically auto healing the code and just working and making the program that you wanted are very low, at least in my experience.

Maybe I'm using it wrong, but obviously there are issues there. And of course it's still a miracle product, but still probably one of the most important things the civilization has accomplished. But I don't know that the rate of progress is increasing anymore. And we're going to get a free lunch because these H100 processors will come online and the new integer format NVIDIA came up with can compute things a little bit faster. And so you're going to get a free speed up on training and inference from that stuff alone without any software improvement. But I think on the software side, right now where I'm sitting talking to you here today, May 1st, 2023, to me it seems like progress is slowing, which of course the AI doomers would say is a fantastic thing. So, whatever, we're not going to get into that debate. By the way, for the investor, I think progress slowing is good and bad.

I mean, it's good because you've got a chance to catch your breath and the market structure's not changing underneath you. The bad news is you tend to place a lot of bets with the preconception that the market's going to look a certain way and it can just change when things pick up again. And I think they will pick up again. For example, you have all these businesses raising huge amounts of money started by fantastic people in my view, that are doing these vector databases. So the idea is to create some type of database like MySQL or Oracle's database that's able to very efficiently search on the similarity of text, which is what machine learning models or these large language models do using their embeddings or whatnot. And that's really interesting if the context window, the amount of text you can input simultaneously into a model, stays fairly fixed.

So you're using these external vector databases as sort of a hippocampus connected with a umbilical cord to the model and it can shuttle things back and forth and it can talk to the vector database like a little external library. But if the context window dramatically increases to 1, 5 or 10 million tokens, I don't know how much vector databases really matter because I can just suddenly, for example, put my entire source code into the context window of the model or put the entire US tax code into the context window of the model. So that's a good example of one of many market structure shifts that'll happen. I think it's a very exciting time and space to be allocating in. The whole market itself is changing, not just the companies, which is really different and speaks to how quickly I think the world is moving.

MM: Wonderful. Well, that was a great answer and it was a delight having you on the podcast, DG. Thank you so much for being a guest.

DG: Thank you very much for having me.

Subscribe for more episodes to come: Spotify, Apple, Google, Amazon, and Overcast.